Your game console talks to Netflix and other sites on the Internet. Your TV, DVR, smart-phone and tablet PC are all capable of accessing the Internet. You may very likely have a smart electric, gas or water meter that is connected to your house and able to talk to your heating and cooling systems. You can buy a refrigerator that can inventory itself and message the grocery store with an order for pickup or delivery. Your tires talk wirelessly to your car's main computer system. Your car accesses the Internet for GPS and other services. In the factory, embedded diagnostics use ubiquitous networking, both wired and wireless, to message maintenance computers and generate work orders. You wear an RFID tag in the plant so that in case of emergency, safety personnel can find you. All of this happens without you pressing one key. All of this is happening now.

They call it the "Internet of Things," and it is already changing the future of the way we live andwork. First coined by Kevin Ashton in a 1999 article for RFID Journal, the name has become widely used, but there are many different definitions of what exactly the Internet of Things is, how it operates, and what is included in its scope.

Just What IS the Internet of Things?

SAP AG, the leading enterprise software manufacturer, defines the Internet of Things as, "a world where physical objects are seamlessly integrated into the information network, and where the physical objects can become active participants in business processes. Services are available to interact with these 'smart objects' over the Internet, query and change their state and any information associated with them, taking into account security and privacy issues."

CASAGRAS, an EU Framework 7 project, developed another definition in 2009: "A global network infrastructure, linking physical and virtual objects through the exploitation of data capture and communications capabilities. This infrastructure includes existing and evolving Internet and network developments. It will offer specific object-identification, sensor and connection capability as the basis for the development of independent federated services and applications. These will be characterized by a high degree of autonomous data capture, event transfer, network connectivity and interoperability."

All the definitions of the Internet of Things have much in common. First is the ubiquitous nature of connectivity, and, second, the global identification of every object. Third, the ability of each object to send and receive data across the Internet or private network they are connected into. This isn't some science fiction story, or a futurist's speculation. It is happening right now.

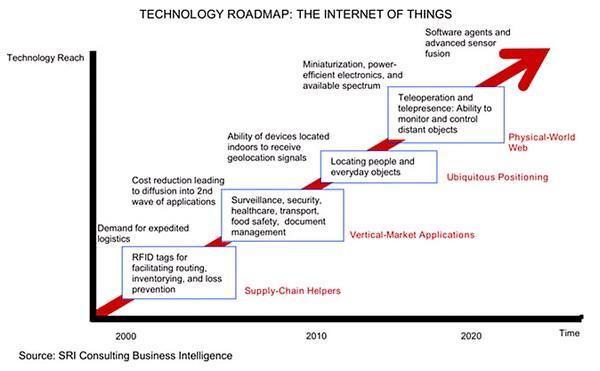

The figure shows what is happening. It started with a demand for better logistics and supply chain management. The second wave was driven by the need for cost reductions. The third wave was driven by geolocation services. The fourth wave will be driven by telepresence, made possible by miniaturized embedded electronic processors, and the next will be the ability to create mesh networks including tags, sensors, process instruments and final control devices.

Bringing the Big Picture Down to Earth

Everyone is beginning to see the Internet of Things developing in the commercial and home sectors. The recent Apple TV commercial for the iPAD that intones, "You will still do…" and lists off numbers of normal endeavors, followed by "You'll just do them differently," is a clear indicator of this. The use of iPads and other connected appliances in business meetings is growing exponentially.

In automation and control, things are not so clear cut. This is partly because of the very long lifecycle of automation systems (up to at least 30 years) and partly because some processes are highly customized. Enough value can be created using Internet of Things (IoT) concepts, though, that plants are already starting to use the technologies.

For example, look at a distillation column. Distillation columns are controlled by temperature. As the hot hydrocarbons rise, they cool to the point where they liquefy and can be drawn off as one or another petroleum product: gasoline, benzene, kerosene, and so forth. The use of inexpensive wireless temperature sensors in large quantities along the length of a distillation column will provide a very large amount of data to the operators that they have never been able to get before—and that can be used for process bottleneck discovery and process optimization. Process optimization data that has never been able to be used before is enabled by the concepts of the Internet of Things.

In a discrete manufacturing plant, consider the value of having parts self-identify with RFID tags, and automatically controlled rolling bins and forklifts moving parts and subsystems around automatically without human intervention—and always getting the right part to the right place at the right time. And then consider the further value of having all that information available in easily accessible databases wherever needed.

Now consider environmental monitoring. Look at the value inherent in having intelligent air, water and solid waste pollution sensors connected to the manufacturing control system, so that repair and remediation are automatically triggered if values go beyond set points.

The IOT roadmap

Finding more case study articles

DIGITIMES' editorial team was not involved in the creation or production of this content. Companies looking to contribute commercial news or press releases are welcome to contact us.