Chih-Kai Cheng, a friend of mine in venture capital business in the US, has remarked that the ethnic Chinese in Silicon Valley have a broad vision but lack practical experience in resource integration. Taiwanese are pragmatic and reliable but sometimes act without visions. People from China think big and bold but often end up with biting off more than they can chew.

In the early 1990s, the overseas Taiwanese were pragmatic and diligent. Returning to Taiwan to purchase motherboards and monitors, they assembled PCs and sold them to local distributors. There were not many technical difficulties in doing this. Price and relationship eventually became the sole elements to win business. In the end, they were driven out of the market by big retail chains, such as Fry's or CompUSA, or even COSTCO. Evidently, operation without economies of scale but price competition is far from the best strategy.

The ethnic Chinese engaged in IT business on the US west coast have a broad vision and are the most courageous bunch of ethnic Chinese to challenge business opportunities brought by the industrial transformation. In the 1990s, they assumed an active role during Taiwan's growth stage, with many people investing in two capital-intensive, technology-intensive industries: wafer foundry and IC design. Taiwan's homegrown talent mostly focused on the mass production of ICT products. They were unrivaled in production management. Starting in 2000, Taiwanese notebook and mobile phone manufacturers began to move to China, which was rising. Cross-strait collaboration was close. That was an age where knowledge and interest took center stage, and ideology was cast aside. Admiring Taiwanese's success, China's homegrown talent followed suit and capitalized on business opportunities from mobile phones. They had experienced phenomenal industrial growth before the US imposed a trade ban.

After 20 to 30 years of experience, Taiwan-bred talent are no longer amateurs. But the concern is how they can pass on the baton. The first generation of entrepreneurs went through trials and tribulations, but they worried about the capability of the next generation. A tyical enterprise is co-managed by executives who make joint decisions. This certainly reflects the industrial development of moving towards a new era of multiple dimensions demanding proper decision-making in technology and marketing. But the CEOs who can elucidate the industry strategy from a macro perspective are a rarity in Taiwan. But sooner or later Taiwan's business leaders will have to face the challenge of developing a "comprehensive vision."

Those who can interpret the game on and off the field and control the situation are exceptional talent. The first generation of entrepreneurs understand that it is a very complicated industry. Most of them are willing to let professional managers take over. This will be an important trend in Taiwan's technology industry.

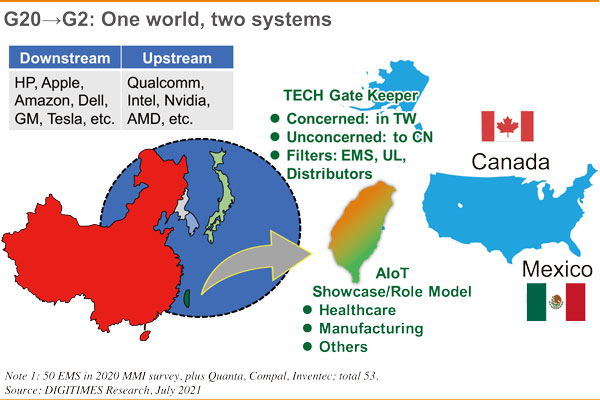

It is not surprising for Taiwan's return to the North American market in addition to the deployments in ASEAN and South Asia. Foxconn has acquired a plant from EV maker Lordstown. With large factories in Mexico, Wistron or Inventech may make moves in the Canadian EV industry in the future.

Making good use of the resources of ethnic Chinese talent in the US will also be one of the keys to Taiwan's success. The ethnic Chinese in the US must understand that Taiwan already has a slew of enterprises of over US$10 billion. Their vision on business management is drastically different from the past.

Now there are more than 800 publicly listed electronics companies in Taiwan, with annual revenues of more than US$800 billion. Taiwan's IT community is capable of funneling in no less than US$150 billion of funds from the financial sector, with no fewer than 800,000 employees. It is an industry of highly professional division of labor that is full of challenges as well as opportunities.

(Editor's note: This is part of a series of analysis of Taiwan's role in the global ICT industry.)